The COVID-19 Vaccine Supply Chain, Explained

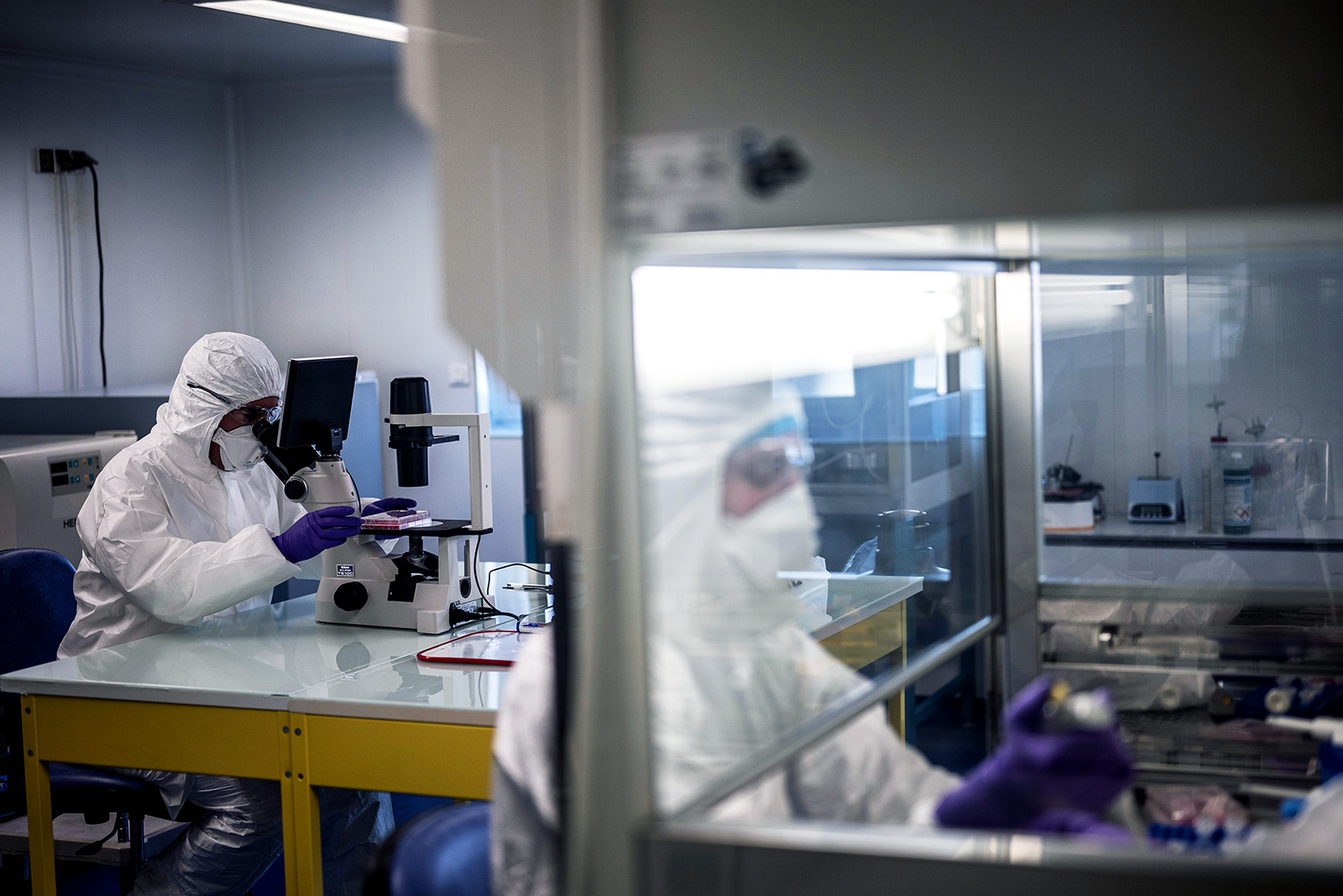

Scientists at work in a laboratory, as they try to find a coronavirus vaccine. There are several supply chain challenges involved in distributing such a vaccine.

Photo: Jeff Pachoud/AFP via Getty Images

Once a COVID-19 vaccine has been approved, the task of quickly getting millions of doses to the American population poses an enormous supply chain challenge. Not only is there likely to be more than one vaccine, but most vaccines in trial will require two doses, and some will need to be kept in ultra-cold storage.

BRINK spoke to Julie Swann, a senior advisor to the CDC on the last national vaccine distribution in 2009 for the H1N1 flu vaccine. She is a professor at North Carolina State University and co-founder of the Center for Health and Humanitarian Systems at Georgia Tech.

BRINK: Once a vaccine has been approved by the FDA, who will actually own it?

SWANN: Once it is approved, the vaccine would still belong to the companies who created it, except that there are a lot of contracts in place where both the U.S. government and other governments have committed a pretty good amount of money to ensure that they get a certain number of doses. And so the manufacturers will begin supplying those doses to the governments that committed that funding.

BRINK: And in terms of the U.S., do you have any sense of how many doses are needed?

SWANN: What we expect is that most of these vaccines will require two doses to be fully effective, separated by approximately 30 days. We don’t know how many people will choose to get the vaccine, but if you take the vaccination rates for influenza as a starting point for adults ages 65 and over, that rate could be well above 60% of that population being vaccinated in a given year.

As a rough cut, the U.S. has about 210 million people ages 18 and over. If 60% received two doses each, that would be more than 250 million doses.

Still Sorting Out Prioritization

So somewhere between 30% and 70% of the American public might eventually be able to take one of these vaccines — and they will need two doses. At the moment, it won’t be approved for children, but I think the goal is to eventually add children in as well.

BRINK: Will all of those doses be available from day one, or will this be a gradual production?

SWANN: In the early days, a small number of doses will be allocated to very specific groups. The prioritization is not fully laid out, and in fact, ACIP (the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices) has stated that the final prioritization won’t be laid out until there’s more information after phase three of the vaccine trials. One reason is that there may be some subpopulations that for whom the vaccine does not work as well.

But the initial prioritization is thought to be healthcare workers in direct contact with COVID-19 patients. And from there, there would be additional priority groups — they could be other essential workers or people above age 65 with high risk conditions. So in those beginning weeks to months, it’s not going to be available for anyone to just walk in off the street and get.

BRINK: Could we see more than one vaccine approved at once?

SWANN: Absolutely. In fact, we expect that will happen. There may be a difference of a few weeks or a couple of months, but at some point, there will be multiple vaccines on the market, and they will have potentially different requirements in terms of the logistics of the cold chain.

The Cold Chain Problem

BRINK: How confident are you that supply chains will hold up and be able to handle these many doses, as well as different types of vaccines?

SWANN: Yes, there are several challenges that make this a really complex supply chain. The number one challenge is the types of ‘cold chains’ that are going to be required. Of the two vaccines that are furthest along — the ones from Pfizer and Moderna — the Pfizer one requires the vaccine to be shipped and stored in -80F conditions. Most of our supply chain does not have that capability currently. So that’s a significant challenge.

One tricky part about having multiple products is that when you get your second dose, an individual will need to get the same vaccine that they had the first time. And so, we will need our information systems to keep up with that and remind people.

People will not trust the vaccine, what’s called vaccine hesitancy, and that would lead to additional cases of COVID-19 and loss of life, as well as continued economic disruptions.

And then we will need different kinds of systems to talk to each other that may not have been in place previously, and the vaccines will have potentially different efficacy levels and other trade-offs. So part of the complexity will also occur at the provider, state and local health department levels, as they determine how much of which vaccine to get.

H1N1 Was a Trial Run

BRINK: You were a senior advisor on the rollout of the vaccine for the H1N1. How useful is that experience in this case, or was there nothing similar?

SWANN: There is a lot that was done during the rollout of vaccines for H1N1 that is similar. It was a test of the system and it showed that it indeed can deliver, let’s say 100 million doses across the United States. In that case, there were multiple manufacturers, and multiple products, and some were approved for children and some were not. So that part of it we’ve done before.

But those vaccines did not require a cold chain that was different than what was already in place for other vaccines.

Hard to Reach Rural Areas

BRINK: As you look at this, before the rollout, what’s your biggest worry?

SWANN: I have four big worries. One is that for vaccines that require these specialty cold chains, it will be more difficult to reach people who may live further from a big city. It will take a lot of time and money to make sure that the vaccine is broadly available throughout a given geography. And that is true, not only in the U.S., but globally.

A second concern does relate to global availability of the vaccine. I just read a report from Germany which estimated that only about 25 countries would be able to handle the infrastructure required for the ultra low cold storage vaccines.

If you think about trying to deliver an ultra low cold chain vaccine in Africa, it may be even more difficult. It has been done — the Ebola vaccine required a specialty cold storage supply chain — but the majority of the countries have not had that.

There’s another aspect that makes logistics difficult. The Pfizer vaccine will ship in a container that has approximately 1,000 doses. And once that container is opened, you can only have it open for a very limited period of time without moving it to a different storage. That means that it would only be appropriate for sites with enough people where it could make sense to send 1,000 doses.

A fourth concern that I have is that people will not trust the vaccine, what’s called vaccine hesitancy, and that would lead to additional cases of COVID-19 and loss of life, as well as continued economic disruptions. This could differ across subpopulations, so it could even lead to greater inequities due to COVID-19.

Public-Private Partnerships

BRINK: Is there a role for other companies to help in this effort?

SWANN: There are great opportunities for public-private partnerships with organizations such as retail pharmacies. Of course, retail pharmacies, like CVS, Walgreens and others, have quite a wide distribution network and they don’t have the ultra low cold storage in every individual location, but they might have that capability at the distribution center.

To the extent possible, anything that can be done to build on the capacity that’s already in the pharmacy supply chain could be helpful in addressing last mile challenges and reducing inequities and who has access to the vaccine.

There are other public-private partnerships that can play a role, too. For example, developing technology to schedule an appointment, or search for availability, or track vaccines to the final point of administration, and provide temporary cold storage, and so on.

BRINK: Do you foresee the U.S. being in a position to export a lot of its vaccines, even though it hasn’t joined the global COVAX coalition?

SWANN: I wish that we had joined COVAX. Eventually there will be enough to export, but it could take the companies some time to fulfill the commitments that they’ve already made before they begin committing to additional countries and exporting more vaccines. I think we are currently missing out on the opportunity and responsibility to help others throughout the world, which could also reduce the impact COVID-19 has on the U.S.